The woodland camo pattern went in and out of vogue for the next fourteen years. In the mid-1970s the US Marine Corps finally adopted it as standard issue before, in 1981, the US Army finally saw the light and it became standard issue for all US Army soldiers. The Air Force and Navy also adopted essentially the same uniform for use in wooded environments. When they were operating in desert or urban environments, there were other color variants, but the pattern was essentially the same.

While the woodland camouflage pattern did its job well, it had also been around for almost sixty years with only minor revisions between the late 1940s and the early 21st Century. It was readily available, proven, and inexpensive, but it was also not the state-of-the-art. None of this would be an issue for the Army or Navy. Indeed, US Navy officers are still wearing khaki uniforms that British Army officers were wearing in the 1880s.** True to form, the service that led the innovation in no-nonsense, practical development of combat gear was the US Marine Corps.

Here’s what they came up with:

The Marines’ digital camouflage pattern (called “MARPAT” because the full name has too many syllables for Marine vernacular) works great. It comes in two colors so far. One predominantly green and brown pattern for wooded areas, and one in shades of tan for desert areas. The uniform includes brown, rough-side-out leather boots that can’t be polished, making them even harder to see. I’ve even seen pictures of Marine cold-weather gear in a predominately white variant of MARPAT camo. Cool.

When they made the upgrade from the venerable woodland camo BDUs to the MARPAT uniforms, I was stationed at Naval Education and Training Center, Newport, RI as an instructor. The new pattern worked so well that within the first month after the switch, no less than three Marines on base were hit by cars whose drivers didn’t see them while they were crossing the street. When you’re trying not to be seen, those are pretty impressive results.

So with the wild, almost deadly, success of the MARPAT camouflage it only makes sense that the other branches would be clamoring to adopt it for use by their personnel who need to go unseen. Unfortunately, the US military does some strange things when it comes to making sense. The Marines came up with their own, different camouflage first. Not to be outdone, the Army had to develop their own proprietary pattern of camouflage as well.

Buying new costumes for everyone in the Army is an expensive proposition though. Especially if you have to worry about buying every soldier a new ensemble to color coordinate with every kind of environment they might be operating in while also accessorizing in ways that won't clash. So, placing budget concerns above practical concerns, the Army developed a universal digital camouflage pattern called “Universal Camouflage Pattern.” The idea was to come up with a digital pattern using colors that would be equally suited to every imaginable location. The result: a pale replication of the MARPAT camo consisting of in-between colors that don’t quite blend in with anything.*** Here’s what it looks like:

For a while this struck me as the stupidest thing I’d seen in the military of late. Then the Air Force realized that their stupid department was falling behind. Rather than adopt either of the well-though-out and expensively, extensively researched patterns of camouflage that these other branches came up with, the Air Force decided they needed to have their own brand of stupid-looking. As a result they came up with their own camo pattern, which they call “digital tiger stripe” while everyone else just calls it “goofy.”

Behold, the "Airman Battle Uniform" pattern camouflage:

Coming up with their own pattern seems to be all the stupid they had to in their budget. When it came time to choose a color pallette, they had to borrow some extra stupid from the Army. The Air Force’s digital tiger stripe camouflage is printed in the exact same hues as the Army’s Universal Camouflage Pattern, colors which still don’t blend in with anything even after being arranged slightly differently.

The pattern itself harkens back to the tiger stripe BDUs that some Special Forces units wore for a brief time in Vietnam. When you’re crawling along on your belly through old-growth bamboo to sneak up on Charlie and slit his throat with your bayonet this pattern makes sense. It makes a bit less sense when you’re strolling along an airstrip armed with a briefcase and/or a cup of coffee. Once again, making sense didn’t figure large in the decision to switch to these uniforms.

The one thing that the Army and Air Force got kinda right though was the boots. They did away with the old, shiny black leather boots in favor of tan (or for the Air Force, minty green) boots with the rough side of the leather on the outside. Apart from that one redeeming quality, these uniforms don’t make much sense to me. They were still among the stupidest things the military had done for a while and ever since I first spotted the Army’s new not-quite-camouflage, I’d been pretty smug about them.

Then it was the Navy’s turn.

A couple of weeks ago there was an article in Navy Times about the new NWUs (Navy Working Uniform). It’s basically the same exact pattern as the Marine’s MARPAT camo and the Army’s Universal Camoflage Pattern, but in shades of blue and grey.

Here’s a file photo of the new NWU from back when they were still trying to decide on some of the finer points:

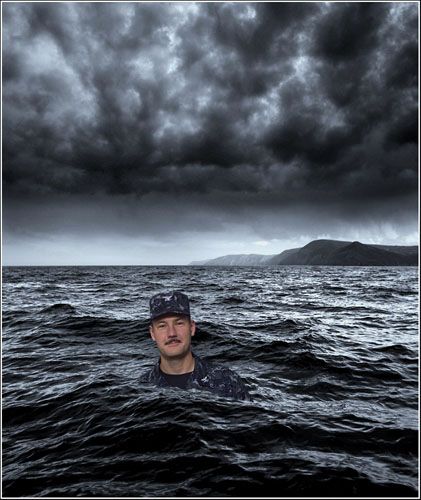

Here it is in a couple of typical operating environments where camouflage might be useful:

The Navy’s camouflage isn’t really intended to blend in with anything. Instead, the color palette was supposedly selected as a way to recognize the nautical heritage of the service. As an afterthought, it also makes it a bit tougher for a sniper ashore to pick you off if you’re out working on deck in port. As an added benefit, one of the colors is “deck gray,” a standardized shade of grey paint used on all Navy ships, so it’s less likely someone will notice if you lean on wet paint. That, and day-to-day grease and food stains will be less noticeable.

The main problem though, is what it will blend in with:

If you happen to fall overboard on a gloomy day, this outfit will make you impossible to spot. So the Navy, in its infinite wisdom, has selected a pattern of camouflage that will only help conceal you in the one rare occasion where you will desperately want to be seen.

Now I realized it’s possible that there are some scenarios where you might be floating along and want to stay hidden. A ship might be torpedoed and sunk by a submarine and, to keep their whereabouts a secret, the sub might surface and kill off the survivors. Or perhaps bloodthirsty enemy fighter pilots might make a sport of strafing shipwrecked sailors. Still, I can’t help but think it’d be better to make the uniforms in some sort of lighter, brighter color that might facilitate rescue.

In the past, the Navy has either clung desperately to centuries-old sailor costumes or worn practical clothing integrated into the safety gear required for the task at hand (i.e. the rainbow wardrobe you find on the flight deck of an aircraft carrier). The NWU is a disappointment in that it’s not in any way nautical, nor is it particularly practical given the environment it’s intended for.

The worst part of all is that it comes with nice, shiny black boots. After all the effort to come up with a supposedly low-maintenance new uniform, sailors will still have to waste time polishing their boots. As a result I now have no room whatsoever to call the Army and Air Force uniforms stupid. This new stupid uniform comes close on the heels of a variety of other new stupid uniforms the Navy has adopted as well as some old stupid uniforms they have resurrected. Now I’m going to have to rush out and buy a whole new set of gear when I get back to the States.

Bummer.

*BDU was the Army’s term for the old woodland camouflage uniform. The Marines referred to them as “Boots and Utes,” while the Navy called them “cammies” and the Air Force called them “our only manly uniform.”

**True story. The word “khaki” comes from the Hindi-Urdu word for “dusty” and the all-tan uniform became standard for British soldiers stationed in India in the latter half of the 19th Century. The US Navy still hasn't given them up.

***I’ve been wearing this particular pattern for about two months now and the only thing that it seems to look like is certain types of gravel. So apart from laying in someone’s driveway, I can’t think of anyplace where this color scheme would help me hide.

On a normal day, fresh from the shower and wearing only a towel, I weigh around 160 pounds. With all of this crap on, I weigh in just under 300 pounds. Needless to say, I take every available opportunity to rest:

On a normal day, fresh from the shower and wearing only a towel, I weigh around 160 pounds. With all of this crap on, I weigh in just under 300 pounds. Needless to say, I take every available opportunity to rest: